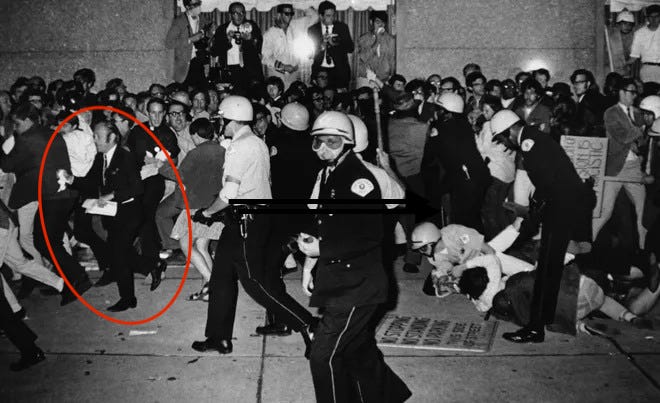

I am looking at a photograph taken on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue a little after 8 on the evening of Wednesday, August 28, 1968, and wishing my father was still around to fill in a few details. It’s a dramatic image. Center foreground is a cop in a riot helmet who seems to be weighing whether to use his night-stick on the photographer, Michael Boyer of the Associated Press. Behind him, moving right to left, similarly accoutered colleagues are chasing people down the sidewalk outside the Conrad Hilton. That’s where Vice President Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic presidential nominee, is headquartered along with his rival, Senator Eugene McCarthy, for the duration of the Democratic National Convention under way three miles south at the (since demolished) International Amphitheater. Wedged between the chase — perhaps mêlée is better — and the wall of the Hilton is an involuntary chorus of deeply uncomfortable spectators. Most would clearly rather be somewhere else if getting there didn’t entail being beaten bloody by Mayor Richard Daley’s enraged gendarmes on the way.

Among the pursued is Dad, dapper in Lob shoes and Savile Rowe suit with silk square billowing from breast pocket. Mother always insisted he be properly dressed. She would not have been amused to see the notebook peeking from his jacket’s side pocket. That’s how you spoiled a good suit’s cut. In his left hand are papers of some sort, in his right a handkerchief to provide rudimentary protection from teargas and the charnel house stench of the stink bombs the Yippies have been tossing about to make some sort of point. A cop a good deal larger than Dad, who was 5’ 3” in his socks, appears to be gaining on him with intent.

Is this the galoot who put my father’s arm in a cast?

I lucked into the photograph because, with the Democrats once again holding their convention in Chicago (rather more joyously this time), it seemed a good moment to dig into this episode of Dad’s life for the biography I’m working on — tentative title: Chronicler — in tandem with the one about my great aunt.

I was 12 when it happened. Dad was the London Sunday Telegraph’s Washington correspondent. My mother and I were holidaying in England at the time and heard about his getting injured from a BBC news bulletin. I was less concerned about his health than thrilled by his fame and derring-do. Mother may have taken a different view. Dad supplied further details in the story he filed for that Sunday’s editions and in person when he joined us, bandaged, the following week. He wrote of it again in his book, America in Retreat, which came out in 1970. For all that, and even though we visited the scene together in 1976 en route to covering that year’s Republican convention in Kansas City, I have been never entirely clear on what went down. So it was wonderful — thank you, Google — to run across a picture that put Dad slap in the thick of things to go with the one I have of him with Mussolini’s corpse in Milan’s Piazza Loreto in 1945.

Let’s take a step back to consider what was happening that day. Tens of thousands of mostly young protesters had descended on Chicago united in their understandable rage against the war in Vietnam and the possibility of being drafted to fight in it. They had arrived under a smorgasbord of overlapping aegises, among them Abbie Hoffman’s Youth International Protest (Yippies), Dave Dellinger’s Mobilization Against the War in Vietnam (the Mobe), and Tom Hayden’s Students for a Democratic Society. Many had come to help McCarthy somehow wrest the nomination from Humphrey. “Dump the Hump!” was their battle cry. Others preached outright revolution and meant, quite openly, to cause mayhem. All, by the third day of the convention, were fully up the noses of Mayor Daley and his boys in blue at whom they had been throwing epithets (“Pigs!’ being a favorite and among the more polite) and a variety of missiles, ranging from bags of human waste to things that can cause serious injury.

At this point, a lot of them were in Grant Park. Daley, who didn’t want them anywhere near the convention proper, thought they should stay there. The main body of the park is bounded by Lake Michigan and Lakeshore Drive to the east and a railroad cutting to the west, on the other side of which, running parallel, is Michigan Avenue. Put riot police or National Guardsmen on the bridges across the cutting and you block access to Michigan Avenue and the rest of the city, at least in theory. By late afternoon, thousands of demonstrators had found their way around or through the various cordons and were seething south down Michigan Ave. towards the Hilton where the Hump was recovering from a collateral dose of teargas and getting ready for his acceptance speech the following night.

The Hilton occupies a full block on the west side of Michigan Ave. facing the park and the lake and is bounded by Balbo Drive to the north. Here the police decided to make a stand to keep the mob from the hotel’s main entrance. On of the corner of Balbo and Michigan was the Haymarket Lounge, to which Dad and other members of the fourth estate had, I believe, repaired for early evening refreshments. Its floor-to-ceiling plate glass windows afforded a congenial vantage point from which to observe developments on the street outside. As the action heated up, the more daring of the journos put down their drinks to take a closer look. They were greeted by a phalanx of police advancing toward them down Balbo.

Marino de Medici of Rome’s Il Tempo, writing 50 years later, remembered:

I saw it coming like the giant wave of a tsunami, mostly policemen swinging batons and hitting people with a ferocity that I could not expect from an arm of the law. Suddenly, I felt that I had become a target and I shared my fear with a colleague standing near me, Stephen Barber of London’s Sunday Telegraph. A few seconds later the arm of the law came crashing down on us, breaking the right arm of Stephen as he was trying to fend off the blow. I was lucky because at that very moment the large plate glass window of the travel agency office facing the street came crashing down. I quickly rushed into the empty space and escaped without injury.

Here’s Dad in his piece for the Sunday Telegraph:

I got beaten up on the pavement outside the Conrad Hilton hotel right after a bright, bearded lad in sandals with the Oxford Book of English Verse under his arm had informed me: “Now you people are going to feel police brutality. I can tell. Just you watch!“

He could read the signs, I gathered. A group of blue-clad men had materialized from a side street. They were pocketing their numbered badges. “That means they are going to get rough,“ the boy said.

Sure enough, it so happened.

The pavement was supposed to be sanctuary. But there were photographers at work. The police made them their prime targets all week. In this case, they suddenly exploded upon us, just as the poetry lover predicted.

I was lucky to fall in the first wave. People behind me – almost all onlookers rather than demonstrators, as it happened – were driven back in such a panic that the plate glass window of a hotel bar [The Haymarket] shattered. A middle-aged woman screamed. The police sailed on, through the window, still swinging their clubs. “They’ve gone mad,” someone said. It struck me as quite an understatement.

It is at this point that Winston Churchill, the statesman’s grandson, Louis Auchincloss, a Kennedy clan in-law, and a young woman, identified by Churchill as Anita Miller, enter the narrative. Churchill, 27, was covering the convention for the London Evening News, Auchincloss for NBC.

Dad’s take for the Sunday Telegraph:

Anyone was fair game – convention delegates included. And to interfere was to risk arrest or a beating or both. Winston Churchill and, Mrs Jaqueline Kennedy’s half-brother James Auchincloss – both reporters – were chased by three or four policeman on foot and another on a motorbike who rode straight over the curb to try and smash them against a railing, simply for intervening to rescue a young girl who was being brutally slugged by a plainclothes man armed with a cosh.

The eyes of these thugs…simply blazed with insanity. There is no other word for it. Hitler’s storm troopers were the same type.

And here’s Dominic Harrod, reporting for the Daily Telegraph:

A well-dressed 20-year-old Chicago girl who happened to be on the scene was run down from behind by a plainclothes policeman from whom she was running, obeying his yell to “move on“. As his baton hit her shoulder and she fell, Mr. Winston Churchill, reporting for the Evening news, and Mr. Auchincloss, working for the National Broadcasting Company, ran towards her.

As she rose, and I was moving towards the mêlée, the plainclothesman darted away across the avenue towards parked police vans. At that instant, a motorcycle policeman hurtled along the road, screeching to a noisy standstill a yard from us, one wheel against the curb, before turning and roaring off across the street again.

Within minutes, Mr. Churchill, Mr. Auchincloss, Mr. Stephen Barber, correspondent of the Sunday Telegraph, and I were picking ourselves up after another charge this time on foot, and comparing baton bruises on heads, wrists and thighs.

Churchill’s version, as paraphrased by the United Press, went like this:

He said he was standing not far from the hotel with Mrs Kennedy’s half-brother when a young blonde girl ran past to escape police attacking demonstrators about 100 yards away.

Suddenly, he said, a plainclothes man dashed across the road, pulled a blackjack from his pocket, grabbed the girl and began beating her.

He said he and Mr Auchincloss went to help the girl. He said he asked the man his name.

“The only answer we got was be be attacked by him also,” Mr Churchill said. “Mr Auchincloss was hit a couple of times and I was knocked to the ground.

“As I picked myself up, a three-wheeled police motorcycle charged the two of us and pinioned us agains the wall near the pavement.”

Mr Churchill said he and Mr Auchincloss clambered over the wall and got away.

Writing America in Retreat a year or so later, my father recalled the scene thus:

I had my arm broken when a helmeted lunatic clubbed me as I watched Winston Churchill and Jamie Auchincloss — both reporters on the scene and scarcely militant radicals — rescuing a young girl from a plainclothes man who was lunging at her with a billy club at least 100 yards from the main mêlée. The girl, we discovered, was not even a McCarthy supporter — she was for Nixon — but that made no difference. As far as Daley's boyos were concerned, it was open season on the young and any who might be presumed to sympathize with them.

In my own retelling over the years — and in spite of knowing better — I have, I confess, often made my father the hero of the piece, having him run to the rescue of both Churchill and Ms. Miller. Churchill died in 2010, the same year Auchincloss went to jail for possession of child pornography, so I have had little fear of contradiction. I now happily spike my version in favor a much better one I found in the memoirs of Connie Lawn, a redoubtable radio journalist and dear family friend we sadly lost in 2018.

At one point, as I walked through the crowds with press tags hanging clearly from my chest, I was the victim of an attack, and thvus temporarily became an unwilling participant in the news, as well as a reporter. The police charged, and one heavy officer slammed his billy club down on my head. His eyes widened with shock and disbelief when the club bounced back at him. Those were the days of the stiff, teased hairstyles and wigs. My own waist length hair was rolled up under such a wig, and it probably was the only thing standing between the billy club and a skull fracture.

One of my colleagues, Winston Churchill II, wasn’t so fortunate. As he and his fellow British journalist, Stephen Barber, strolled through the park that night, Churchill also found himself on the receiving end of the billy club treatment. Barber, desperately trying to rescue his friend from the battering, yelled at the cops, “You can’t hit him – he’s Winston Churchill!” “Right, buddy,” one of the cops sneered, “and we’re the tooth fairy.” They began hitting him even harder, breaking his wrist in the process.

Here’s the full chapter from America in Retreat featuring the Chicago rumble. It’s entitled Turning Right and Turning Inwards.

Nixon entered the White House in January 1969 as the quintessence of middle-class, middle-income America — the champion, as he sees it, of the “silent majority” of the non-Black, non-young, non-trendy and non-poor: the people who go to Church most Sundays, pay their mortgages, agonize over their incomprehensible children, worry about inflation, the rising crime rate, drug addiction, and pornography, and detest the Vietnam war but find it hard to face losing it. They were fed up with race riots. The gold drain perplexed them. Foreigners seemed to be losing respect for the dollar. It had, surely, been different under Eisenhower — and here was Nixon, blessed by Ike from his sickbed and with the national father figure's grandson, David, betrothed to his daughter, Julie. His nomination had taken place at the Republican convention at Miami Beach — the archetype of all that is most stridently vulgar about affluent suburban America and its values, a man-made redoubt constructed of neon, concrete and polyethelyne on sand, isolated from uglier realities by a polluted lagoon. America was tired and fretful — not least of all about her world role.

In public, Nixon naturally talked about “making the American dream come true” and foreseeing a day when “America is once again worthy of its flag…(and) of respect.” But underlying the tub-thumping was a hard core of realism. He had shelved any idea of “winning” a military victory in Vietnam. In private — and before he was nominated — he was amazingly candid about it. At a closed session of party delegates, which was surreptitiously tape-recorded by the Miami Herald at the time, he let the cat out of the bag. Someone had asked him, he said, if he thought the war was lost. “I said that if I believed that, I won't say it. The moment we say the war is lost you're not going to be able to negotiate, you see. The only way...is to convince the enemy you've some strength left.” He then went on to claim he would get out of Vietnam the way Eisenhower had from Korea — by negotiating and making the South Vietnamese strong enough to permit a US withdrawal. And “regarding the future, there won't be any more Vietnams!” he promised.

Similarly, Nixon unveiled his intention to duck the world policeman commitment. He was most warmly applauded when he talked about getting the allies to share the load “so we don't fight their wars for them”. As for Russia, he was for telling its leaders that as neither they nor the US wanted nuclear war so the time had come to negotiate. 'We've got to broaden the canvas from Vietnam — they have no reason to end that war. It's hurting us more than them,” he said. “But we could put the Mideast on the fire. And you could put Eastern Europe on the fire. And you could put trade on the fire. And you could put the power (sic) bombs on the fire...and you say: “Now, look here. Here's the world. Here is the United States. Here's the Soviet Union. Neither of us wants nuclear war...They want something else but they don't want war.”So they'll say: “What are we going to do in order to reduce these tensions?”” There was, needless to say, not a word about keeping the allies informed in any of this.

Nixon's vision sharply differed from that heroic Camelot-by-the-Potomac of the Kennedy era. It was a vision unlikely to charm the young, the poor and the Black, who remained a minority in this land for all the noise they made. America suddenly seemed middle-aged, having reached that condition in record-breaking time, compressing British imperial experience of a century following Trafalgar into not much more than a couple of decades. The nation was quietly throwing in the sponge. The Democratic Party Convention in Chicago of 1968 saw Nixon's opponents locked in bitter battle over the Vietnam issue. Nixon himself was already determined to withdraw from Vietnam as rapidly as he could. There were no longer any hawks in the running — only variants of doves. Even the third party candidate, former Alabama Governor George Wallace, while picking General Curtis LeMay as his running-mate, took very good care to insist that he felt America should never have got into the war in the first place and that he, too, would never keep “American boys” over there indefinitely. The plain, unvarnished truth was that the nation wanted to get out of Vietnam. There was no longer the faintest echo anywhere of Kennedy's famous pledge “We shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship…to assure the survival of liberty.” Nor was anyone for carrying on as Johnson's “guardians at the gate”.

What occurred at Chicago, therefore, was a 'happening' that could have easily been avoided. The spectacular collisions between Mayor Richard Daley's police riot squads and demonstrators outside the Hilton Hotel, where both Vice-President Hubert Humphrey and Senator Eugene McCarthy were headquartered, were pure guerilla theatre, along with the sideshow riots in Grant Park and elsewhere. They were a way of letting off steam. It was plain enough that the militant activists of the emerging New Left — the Mobilization Against the War in Vietnam, or Mobe, and the Youth International Party, the Yippies — were spoiling for trouble. They wanted to prove that the whole system was rotten, and that the only thing to do was tear it down. Theirs was the “politics of confrontation”. As a studied insult to their elders, the Yippies nominated a pig named Pigasus for the Presidency of the United States. National flags were burned. Communist flags were brandished.

By making common cause for the moment with the frustrated McCarthyite youngsters, the New Left calculated that they, too, would become imbued with hatred for the cops as “fascist pigs”, “enemies of the people”, “baby burners” — to cite a few milder epithets employed — and become converts to the revolution. When the police behaved badly in their turn, which was entirely predictable in a force that is notable for indiscipline and corruption even by American standards, the young nihilists and their allies were delighted and exultant. Public sympathy swung to the side of the police, which shook liberal commentators to the core. As something of a connoisseur of civil disturbance, I reckon the mayor muffed it. Had Daley and his police chief had the wit, they would have profitably permitted the motley demonstration on the main day of the Convention to march on the hall in the Chicago stockyards, as its organizers wished to. It was a hot and sticky August day. The distance was some five miles. Moreover, the route would have taken the long-haired collegiate and predominantly middle- and upper-middle-class pacifists, with their outrageous slogans and North Vietnamese flags, right through an area of the city that is largely inhabited by working class “ethnics” who tend towards superpatriotism. Unlike the affluent, the children of these folk have enjoyed less opportunity to dodge conscription for Vietnam by extending their education year after year and securing student deferments. These were Daley's people. They are the sort that hang out the stars and stripes from their front porches. Had the Yippies and the Mobe led the Minnesota Senator's children through their streets, the scenario would have been rather different: Chicago's police would have appeared on the nation's (and the world's) televison screens protecting the misguided offspring of the over-privileged from the righteous wrath of the less so.

As it was, the police went berserk. They cracked not only demonstrators over the head but onlookers as well. I myself had my arm broken when a helmeted lunatic clubbed me as I watched Winston Churchill and Jamie Auchincloss — both reporters on the scene and scarcely militant radicals — rescuing a young girl from a plain clothes man who was lunging at her with a billy club at least 100 yards from the main melee. The girl, we discovered, was not even a McCarthy supporter — she was for Nixon — but that made no difference. As far as Daley's boyos were concerned, it was open season on the young and any who might be presumed to sympathize with them.

More serious than the mayhem on Chicago's streets — and far more damaging to the Democrats — were Daley's strong-arm tactics inside the Convention hall. He packed the stands with supporters, harassed antiHumphrey delegates and tinkered with the public address system to gag them. It was all so blatant, the Republicans were overjoyed. Nixon was reputedly beaten in 1960 largely because Daley's well-greased party machine in Cook County carried the day for Kennedy by wholesale fraud, stuffing ballot boxes and generally rigging the vote in the time-honoured way. This practice is — or was — an accepted feature of Chicago life, as in other big American cities, even if it is slowly dying out. Daley wanted Senator Edward Kennedy, as a fellow Irishman, to run: when he would not do so, he transferred his loyalty reluctantly to Humphrey.

The uproar at Chicago was both a cause and effect of the growing alienation of America's brightest youngsters. Long before Chicago one began to encounter the phenomenon of “turned off” American student youth. Even as McCarthy's children's crusade was in full swing, I met angry young SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) adherents who regarded the adopted leader of the anti-Johnson movement as a fake. They would tell one without equivocation that in their view American society was so hopeless that nothing would do but to scrap the entire “power structure”, McCarthy included. When asked what they would wish to see replace it, they would reply that any attempt to answer that question must of necessity “institutionalize” the revolution, which would mean creating another “power structure” that would be as bad as that which preceded it. An alternative to this somewhat self-defeating line of reasoning occasionally advanced went like this: “Why should we tell your generation what we want? If we do, there is a chance that you will seek to corrupt our revolutionary purity by proposing a seductive compromise!”

The popular idols of those who indulged in this circular dialectic were, of course, Che Guevara, the Cuban-Argentinian lieutenant of Fidel Castro, who being dead could not betray the cause by contradicting any propositions advanced in his name hereinafter, and Herbert Marcuse, the ex-German political scientist of San Diego, whose works are almost unreadable and hence seldom seem to have actually been read by his disciples. Then there were Maoists, with the little red book, and dozens of other schisms and factions too numerous to mention or bother about. The most fanatic of all to emerge thus far was a small but wholly violent group who called themselves the Weathermen, a few score of whom deliberately staged “four days of rage” in Chicago in the autumn of 1969 during which they smashed up cars, windows and shop fronts in a frenzy of violence, the sole object of which was to provoke “the pigs” into blazing action with CS gas and night sticks flashing. The police duly obliged.

It seems almost incredible now but as late as 1964 it was fashionable for American educators and liberals generally to deplore the conformist tendencies of the nation's youth. They were insufficiently politicized, the complaint ran. The assassination of John Kennedy had numbed them and LBJ lacked charisma. A sense of cause began to develop with the passage of Johnson's civil rights legislation. A number — never very large — felt impelled to missionary efforts amongst the downtrodden Blacks of the deep South, helping the hitherto disenfranchised to register to vote and taking part in various protest marches — often at considerable physical risk. But it was not until the spring of 1965 that the so-called Free Speech Movement was well and truly launched on the University of California's sprawling campus at Berkeley, San Francisco, by a 22-year-old New Yorker named Mario Savio.

Savio, who had been busy as a civil rights activist in Mississippi, announced that he was “tired of reading history — I want to make it!” He organized a series of protests, boycotts, sit-ins and the like, not only for free speech, which meant plain foul language for its own sake, but also, for banning the bomb, against the Vietnam war and denouncing Alabama's Wallace. It culminated in a victory of sorts in forcing the resignation of the university's president, Clark Kerr. There were also clashes with police. Politically it produced the opposite of its intention — a sharp swing to the right in California with the election of Ronald Reagan as law-and-order Republican Governor.

Earnest analysis of this early unruliness, which in due course spread eastwards back across America, have tended to put it all down to the frustrations of the computer age. They saw the student as being increasingly crushed by the exacting demands of specialization. The bigger US universities are so vast that it is impossible for professors to know or even to meet personally more than a fraction of the boys and girls they teach. It is not uncommon, for example, for 2 000 students to attend a lecture in some vast hall while yet more, often scores of miles away on another campus, are sitting in on the same performance piped in by closed-circuit TV. Several State universities boast 30,000 or more students. The feeling of being little more than an automaton in a network of irrelevant studies controlled by punch-cards fed to master automata is easily acquired. Then there are the social and parental pressures on the American child to “make the grade”. Since already one half of the youngsters who emerge from the secondary school system are expected to go on to college it flows inevitably from this that a mere bachelor's degree is scarcely a passport to a good job. Indeed, the latest phenomenon is that PhDs are in serious over-supply. This in turn is making it more important to go to a prestige college than to win the highest qualifications a less well-known one can confer.

Students tend to be particularly disaffected in the Arts and social sciences — the soft disciplines. Not only do many students doubt whether what they are being taught is worth knowing, but so do some oddly assorted elders. Spiro Agnew, the vice president Nixon picked with uncanny skill to function as his political lightning conductor, is one. Gore Vidal, the novelist, is another. Agnew thinks that overemphasis on higher education is denying many a potentially good plumber useful earning time. Vidal thinks it serves as a means of fudging employment statistics — a parking lot in the passage from childhood into life. Educators, needless to say, disagree — and with one another, too.

The problem is compounded, if not caused, by affluence — the same affluence that permits American middle class youngsters to indulge their whims in experimenting with marijuana, LSD and other more dangerous hard drugs to the degree that it is now becoming a real menace in secondary schools. Parental control, never a strong point with the beneficiaries of Dr Benjamin Spock's popular pediatric teachings, is minimal. American youngsters often seem actively to despise their mothers and fathers — certainly to a much more evident degree than in, say, Britain. The generation gap is real. Not only that, but such wiseacres as Dr Margaret Meade, the anthropologist, who ardently supports the cult of youth-knows-best, testify that it is inevitable and right that it should be so.

It can be argued that the child is right to question whether it is worth so much effort to attend his classes in order to end up in the kind of dead-end job his father holds down. The computer age is palpably reducing a widening range of middle and upper-middle executives in business and government into little more than mechanized clerks. The function of decision-making, which alone distinguished the salaried white-collar worker from lowlier, wage-earning office help, can increasingly be turned over to a data-processor. For example, whereas once upon a time it was up to a local bank branch manager to judge a customer's creditworthiness in respect of a loan for a new car or improvements to his house, nowadays he is not encouraged to do anything more than feed the required information on to a card for the benefit of a centralized memory bank, which makes its ruling in the form of a 'read-out'.

When a dock worker loses his job to a fork-lift it is seldom before his union has succeeded in coming to terms with management. This has been the pattern in getting automation accepted in America much faster than elsewhere. The union agrees to accelerate retirements in return for management's contributing large sums to its pension funds, for example. A bargain is struck. The docker who is duly found redundant has fewer illusions about his place in the scheme of things. He is content to go fishing or start a new career in some other field. But the educated executive, shunted aside by the cybernetic age, is emotionally less able to cope with it. How do you tell a man who has been earning $15,000 a year or more and has his name on the glass door of his cubicle that a thing of plastic tapes, whirling discs and ciphers has effectively displaced him? But his son may interpret the message only too accurately.

The modern American child, too, to an even greater degree than his European counterpart, is apt never to have known a situation where three meals a day failed to materialize. His parents may bore him with reminiscences of the Depression years or the War. He will half heed them, if he heeds them at all. He is, in short, pampered and spoiled, much more indulged than loved. On top of this, he — and his sister — are constantly exposed to the mendacities of high-pressure advertising on the TV and in the Press. They are endlessly regaled with news and comment that reveals politicians as charlatans, crooks, self-seekers — and very many indeed certainly are. They cannot visit the drug store news stand without being confronted by the assumption that their entire generation (and a good part of the nation) is sex-obsessed or queer, high on pot and copping out. Lawlessness and corruption is condemned by the same elders as condone it — and profit from it. They perceive on all sides abundant evidence that the society they are expected to inherit is a very sick one, whose values and priorities are in a terrifying tangle.

The youngsters, who turned to McCarthy as a kind of Pied Piper in 1968, found in him a safety-valve for their pent-up frustrations. It often struck me watching him that they invented him as a symbol rather than that they followed him. He would have made a very strange President if by some astonishing miracle he had been elected. His philosophy of office was so excessively low key he would have been well nigh invisible. He would frequently remark, for example, on how he felt the White House should be turned into a museum with the fences torn down. Except that he was thoroughly against the Vietnam war, he was dispassionate to the point of vacuum on most issues. He could also be bafflingly recondite before mystified audiences. I once heard him deliver a fearsomely technical lecture on the problems of international monetary liquidity to a convivial gathering of master builders and their wives in Wisconsin. It can hardly have won him many votes. But the kids, although sometimes in despair at these antics, adored him to a point where it began to worry responsible adults in his party: what on earth was going to happen to them when the adventure ended?

In the eyes of America's well-to-do liberals, the unrest in the nation's schools is largely due to Vietnam. This may be so in their schools, perhaps, but in poorer districts it is more due to racial tension and crime. The common denominator in both is an alarming growth in drug addiction amongst the young. I would not suggest that a mafority are nowadays “hooked”, but rather that it is fashionable both in the ghetto and in white suburbia to be hip to the drug scene. A quarter-million kids slept out at Woodstock at a mass folk music concert, in their bell-bottoms and beads. They experienced the great universal love-in feeling of cause and solidarity by marching on the Washington monument to protest. All this may sound as harmless as Beatlemania, but American children do not do things by halves. The pot cult became almost conformist. Spot-checks of public and private schools all over the country in 1969 showed that scarcely any were free of this drug problem and one-in-ten was seriously worried about heroin. Senator Tom Dodd stated in Congress in January 1970 that drug addiction had become the principal medical problem in the US armed forces and that, at a conservative estimate, 12 million Americans have taken marijuana and 250, 000 are addicted to heroin.

The “Woodstock nation” was not quite as sweet as it had seemed at first. Time magazine reported on the pop festival in August 1969 in ecstatic terms. It “turned out to be history's largest happening,” the paper recorded, “…the moment when the special culture of US youth of the '60s displayed its strength, appeal and power…may well rank as one of the significant political and sociological events of the age.” In fact, this lionizing of a counter-culture spawned by the flower-people of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury and cemented by hard rock music and dope was a foolish attempt on the part of the over-30s to participate vicariously in the seemingly enviable freedom of Youth. Americans of the kind that get to be magazine writers and editors are mortally afraid of seeming square. And doubtless this accounts for their failure to record subsequently that Woodstock died five months later at Altamont outside Berkeley, California, when an attempt to repeat the magical rally ended hideously. It was estimated afterwards that 500 000 turned out for this second concert, stars of which were Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones. Someone had engaged the notorious Hells Angels — a gang of motorbike-riding thugs — as guards. This in itself was enough to guarantee tragedy, which came surely enough. Four youngsters were killed. A Black boy was ritually stabbed to death by Angels right under Jagger's nose as he sang 'Sympathy for the devil' on stage. Over 100 were beaten up by these same hoodlums with clubs and chains. Perhaps 1000 were treated for LSD overdoses. At least two performers were hospitalized — one of them a pregnant girl singer. Time magazine, having waxed so eloquent about Wood stock earlier, overlooked its Californian sequel which was surely quite as “significant...of the age”.

It is not my purpose to moralize about drugs. Suffice it to say that youngsters who take even the soft drug do so partly because it is socially accepted but more so because it releases tensions — and it is, in turn, this which they have turned into their excuse. The slum dweller is buying oblivion from his miserable surroundings, and then resorts to robbery with violence to pay the pusher. The better-off suburbanite seeks release from the hang-ups that derive from inner conflicts of a more sophisticated kind. The fact remains that the entire hippie/youth revolt/ghetto riot/crime-in-the-streets/drug scene is stirring up a powerful groundswell of reaction in Middle America against the young—its own young included.

Dr Calvin Plimpton, head of the excellent, if expensive, New England private school named Amherst, recently wrote an open letter to Nixon ascribing the “turmoil on the campus” to the failure of political leaders to address themselves “effectively, massively and persistently (to) the major social and foreign problems of our times”. He was doubtless sincere — and was much quoted in prestige newspapers — when he said the uproar in the universities “derives from the distance separating the American dream from the American reality”. This is a factor and I have touched on it earlier. But in my view it has been the hypocrisy of teaching the young for so long that the dream and the reality are one that has created much of the problem. Dr Plimpton's Amherst statement had it that “huge expenditure of national resources for military purposes...the critical needs of America's 30 million poor, the unequal division of our life on racial issues” are responsible for the “malaise of the larger society”. It is probably much truer that his more idealistic students — one of whom is David Eisenhower, Nixon's son-in-law — find it impossible to square dropping napalm on Vietnamese villagers in order to save them from Communism as part of an imperial mission with the anti-colonialist tradition they have been led to believe are their heritage. A less inhibited and probably larger group is just as badly disturbed over the failure of American armed might to produce instant results.

Here, then, one comes to the other ugly factor emerging in American politics. Nixon was more haunted in 1968 by Wallace than by Humphrey. George Wallace took 13.5 per cent of the popular vote nationwide and won the five solidly segregationist States of the old South where the American Civil War lives on. There can be no greater mistake than to ignore the phenomenon of his support in the North also. Wallace goes down very well amongst the natural enemies of the better-off, better-educated McCarthy kids — who are to be found amongst the other half of the secondary school output that does not get to go to university. The poor whites of the South and the blue-collar workers who live in big city suburbs in the industrial regions of the Middle West, for example, feel threatened by the advances Black Americans made under Johnson. They know that Blacks moving into the house next door as a result of anti-discrimination laws knocks down the value of their mortgaged homes. Tell them that this will only be temporary and that in due time the problem will iron itself out and you are not apt to get their votes. They also know that the forced integration of State schools depresses educational standards even if this should not be so in theory. It is easy to be liberal, they argue bitterly, in a lily-white suburb or if one is rich enough to send one's youngsters to fee-paying institutions.

Nixon may still be haunted by this Wallace spectre. If anything should complicate Nixon's plan to disengage from the war, he will be in deep trouble — and so will America: a country divided against itself, full of doubts and fears and looking inwards. The tide may well be turning away from acceptance of the policy recommendations of an educated elite — and against the elite. The day of the simplistic know-nothing yahoo may be dawning.

Share this post