I am just back from a couple of days of thrarrghing around the hills and hollows of southern and West Virginia with my friend Roland, he on his Harley, I on a BMW whose early years were spent under the bum of a New Mexico Highway Patrolman but which remains remarkably lively, nonetheless. In the course of our rundfahrt, we visited my parents. They are buried on a wooded ridge above the headwaters of the James River, he in a traditional casket, she, or more precisely her ashes, in a bottle of Roederer, her favorite champagne. How she came there is a story for another day. Today I will tell of his interment. Or rather, I will have James Srodes do the telling. Jim, also no longer with us, dammit, and his wife Cecile were a huge and much loved part of my parent’s life and mine. His roots were in middle Pennsylvania. He and my father committed journalism from the Washington office of the London Daily Telegraph where dad was bureau chief until, just 58, he died in harness in the early spring of 1980. Both of them were among the best at what they did and they had a lot of fun doing it in each other’s company. What follows is, I hope, self-explanatory. Of Donald Anderson and Daniel’s Mountain, I shall have much more to say. Don included Jim’s letter in his unpublished memoir, Before the Break of Dawn.

.

1366 National Press Building Washington, D.C. 20045

April 8, 1980

Dear Mom,

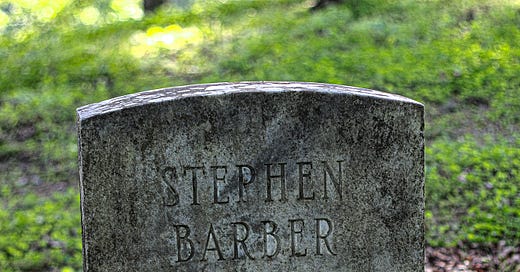

I hope you don't mind but this is a round-robin letter to Nigel Wade, Alan Osborn and Karin Swiers who all knew and loved Steve Barber as much as we did and who would be interested, and I hope take some comfort, in the following report of his funeral.

I don't know if you ever met Steve's friend Donald Anderson. When Steve and Deirdre first came to Washington in 1963 they lived in an apartment complex down in southwest Washington and met Donald, who at that time was an aide to Adam Clayton Powell. It was rare enough for anyone to have a black friend in the Washington of 1963 and, I think Donald would agree it was a rare thing for a black man to have a friend like Steve at any time. In the years that followed the Barbers were frequent visitors at a farm Donald had built down in the Virginia foothills. The home was on a mountain in a quite extensive bit of property that the Andersons’ white master left his slaves back in the 19th Century.

At any rate, when Steve first fell ill but appeared to be recovering, he and Donald fell to chatting and when the conversation drifted around to it, Steve opined that he doubted that he would want to be buried back in England; that he really considered America his home. At that point Donald offered the use of his family burial plot on the hillside of that lovely mountain. Andersons dating back to 1822 are buried there and Steve was mightily amused at the prospect of being the first free-born to buried there. And there the matter rested.

So it was last Thursday that we took Steve to Daniel's Mountain. Simon, Deirdre, her other son Charles McLaren, a nurse from the hospital who had grown fond of Steve, Cecile and I, Hugh and Liz Davies from the office and Congressman Wyche Fowler, who has Andy Young's old Congressional seat and was a longtime friend of Steve's and of Donald's. Gawlers’, the Washington funeral home, brought the casket down and the Davies and we brought the overflow of flowers in a rented station wagon. Our trip was marred somewhat by Hugh s inexperience with a car that big and with American super highways where the trucks whiz past at a high rate of speed and finally he came all unstuck when his erratic driving earned him the attention of the Virginia Highway Patrol, a ticket and a good old fashioned you're-in-a-heap-of-trouble, boy, lecture. For someone like myself whose sense of manhood is inextricably bound in the skill with which one drives motor cars, the experience was a trying one for me. Then we arrived at Daniel's Mountain and the fun began.

The rutted, washed out track up to Donald's farm rose at a 50 degree angle with a steep drop off at the left down the side of the mountain. We could see the gashes on the hillside to our vright and the tire gouges from where the hearse had preceded us and fully expected to see it on its side several hundred feet down the slope. Not so, however. For when we reached the top there were two drivers smoking as they leaned up against the muddy, branch-scraped side of their "coach" (everything is euphemism in the funeral business — hearse is coach, death is inevitable, the deceased is referred to by the first name and the coffin is now called by its brand name style, e.g. The Monte Carlo with the Tufted Taffeta Lining).

"Oh, my God, look what's happened to Hammersmith,” Cecile cried and I almost passed out. Deirdre's one consolation through it all had been her good natured silver grey Weimaraner which was being brought down for the funeral after three weeks in a kennel. And there he was...with his right hind leg cut off at mid-thigh. Except that it wasn't Hammersmith but Victor, Donald's dog who had been getting around on three legs in fine fashion and was waiting to play with his good friend Hammersmith who had not yet arrived.

Catching our breath, we recovered in Donald's modern cabin in the sky, looked down the sunny valley which was just turning green, marveled at his white peacock and inspected the cemetery where we found that the hole was too big to accommodate the automatic rope and pulley mechanism that lowers the Walnut Tudor with Percale Lining after committal.

Moreover, in backing the truck through the trees to get to the hole, the firm delivering the cement vault in which the Tudor etc. would be deposited, cracked the vault against a tree and knocked a big chunk out of it. Another vault was sent for from the Clifton Forge plant and it was agreed that we would move the ceremony from the graveside to a pleasant hillock overlooking the valley and then after taking Dierdre back to the cabin, shift Steve to his final rest.

Say what you will about the Funeral Industry, they give good value. In our innocence Simon and I had contracted with a D.C. firm merely to transport Steve and did not specify anything else. A Clifton Forge lodge brother joined our service by providing the vault. Neither had any interest in cooperating with the other, both pitched in right away when they saw we knew nothing about what we were doing and within minutes a decorous awning was up, artificial grass was laid, folding chairs were placed and covered with a felt covering and after we placed Steve, the flowers were banked into a truly lovely sight, what with the valley spreading out below the blue sky. It was marvelous.

And so was the funeral service itself. Donald recruited Pastor Davis from his local church and we were treated to a genuine Afro-Baptist call to rejoice in the wonderful life of a dear friend who was now gone from this earth but whose memory remained to urge in each of us that each day is a precious gift. Life, Pastor John Davis said, is a moth fretting at the cloth of immortality: he can never succeed. Throughout Victor and Hammersmith romped among us, peeing on the flowers, rolling luxuriously in the warm leaves and causing us all to choke back tears from the sublime marvel of the scene. How Steve would have roared. It was a theme we would repeat throughout the day. How he would have loved it all.

FOOD, of course, is an important ingredient in any funeral. Donald had had a delicious corned beef cooking throughout the day and Hugh and I volunteered to get the cooked cabbage from Donald's cousin — Mrs. Arbulla Mack — who lived over on the adjoining mountain top. By the time I had pushed Donald's tiny VW over the second bridge consisting of two simply laid tree trunks across the stream, Hugh was making small animal noises in the back of his throat. Mrs. Arbulla Mack lived up a 60 degree hill in a tiny house where she had lived most of her 81 years, the last 20 alone, gardening, sewing and cooking the finest cabbage on the Eastern Seaboard.

"Welcome to hell's half acre," she shouted to Hugh, who promptly fell in love with her. "Now you be careful, this has been cooking all day and it'll scald the pee out of you.” And then she laughed and laughed until we had bumped down the hill out of sight. She had already told Donald earlier in the day to convince Deirdre that Steve was "in a better place and had laid his burdens down and was waiting for us to catch up with him".

Interestingly, after a journey to Mrs. Arbulla Mack's, the road to Donald's house looked like a highway by comparison. We returned to find Donald stripped to the waist playing a lament on his bagpipes. His first interest in the instrument was awakened when he was a student at the London School of Economics, and at this point he had been playing the pipes for nine years. He paced slowly across the front yard of the house while everyone took turns freshening Deirdre's drink and insulting Donald's vanity about his well developed torso.

At one point the menfolk slipped away to help shift Steve. A new vault had arrived and it was suggested that we put the coffin in the vault and then lower the vault on the truck pulley into the hole. We sweated and strained and finally after crushing a few fingers we got the Walnut-and-so-on into the cement vault. The lid was placed and the pulley began to lift the vault off the ground as the front end of the truck rose higher and higher off the ground and finally snapped the suspension, pitching the vault and coffin on its side toward us in a swinging arc that had about two tons behind it. With one horrific gasp we all lunged at the box, steadied it, lowered it back to the ground and unchained the truck which was driven away in disgrace. All this, mind you, with the dogs romping, Donald's pipes keening, sweat pouring and us alternating between tears and gales of laughter as we became convinced that Steve was amusing himself mightily at our clumsy efforts.

A larger truck was obtained. We were all by now quite drunk. Donald was quite bug-eyed from playing laments to distract Deirdre from coming back to the cemetery and dogs were showing no signs of slowing down. The peafowl began to scream. "He's doing it on purpose, you know," Charles McLaren said to me. "He's toying with us." I agreed readily. Steve's laughter was almost audible. Finally we got the vault lowered into place and the two slackjawed local yeoman who had been assisting us stepped calmly onto the vault top and began dropping the clods of earth into the hole just as Deirdre got bored with Donald and came around the house to see what we were doing. With a whoop of tears she fled back into the house. Later when she walked up to the horse stables and saw that Donald had converted the damaged vault into a watering trough for his horses, she was recovered enough to laugh with the rest of us and agree, Steve would have loved it.

The rest of the day dissolves into a haze of images. The fireplace, the laughing and the tears, the smell of cabbage and corned beef, the cry of the peacocks, the James River below in the valley, the noise of the freight train out of sight in some other hollow. The four of us left at an early hour that night and slept down below in a motel on the highway. We rose at dawn the next day and drove back in silence.

There really was not much to say, after all. Steve is gone. We buried him on Daniel's Mountain in a way that would have pleased him mightily: for all the amateurism and macabre gaffes, it was an act of love and that is all that counts.

Love, Jim

Share this post