I often wonder what became of the girl we ran over on the afternoon of Tuesday, August 8, 1967, somewhere between Troy and our tent by the Hellespont. She would be about 70 now. Does she have grandchildren? Has she told them how she got that dent on her forehead?

I recently found a photograph — a Kodachrome slide — that must have been taken shortly after it happened. Blotched and faded, it has a dreamlike quality. We are in the middle of nowhere. You can make out a dirt road. On the left is a shelter, a sort of yurt woven from sticks and dead leaves. Next to it are a boy in blue and a girl in a white bonnet. They are looking at a man who is looking at something at his feet. Behind him is our Morris 1100 and three other figures. Assuming my father took the picture, I would be one and the others would be my mother and Charlie, my half brother, 18, just back from herding sheep in Australia.

It was harvest time, “when the sun burns the skin”, as Hesiod puts it, and you had better not sleep in if you want to fill your granary. Nothing much had changed here in the two and half millennia since the author of Works and Days tried to instruct his feckless brother Perses. Had we passed in the cool of the dawn, the fields would have been bustling; in the midday heat, everyone was drowsing in the shade. Except for an English family on a camping holiday, plus, if you believe Noel Coward, the occasional mad dog.

The Morris was not a Land Cruiser. It had already taken a lot of punishment hauling us 2 000 road miles from rural Suffolk and still had to get us back. It was, furthermore, the product of a state-owned company whose employees could only be trusted to do a decent job on Wednesdays, the four days on either side being too close to the weekend to ensure everyone’s full and sober attention. The glue stains on the headliner suggested that ours might have been Monday’s or Friday’s child. So we weren’t tooling along at more than a cautious 30.

I had my nose in a book when the girl ran out from behind the shelter in the picture. Dad hit the brakes. There was a thump. I looked up in time to see her cartwheel off the bonnet and disappear over the roof. We crunched to a stop and leapt out. There she was in the ditch, silent and bleeding copiously from her head. To my panicked 11-year-old eyes, she looked very dead. Stoicism I reserved for Temple Grove, the boarding school from which I was on summer parole. Now I bawled like Hilaire Belloc’s Lord Lundy. I had heard enough of local mores to feel certain we were going to rot for the rest of our lives in an Ottoman oubliette. Mother yelled at me to dry up.

We had set out a fortnight earlier. There was that of Steinbeck about our equipage. The tent mother had acquired for the expedition, a capacious enough pavilion when erect, came in a pair of decidedly ratty sackcloth bags tied with string. Strapped to the roof of the diminutive Morris along with a couple of suitcases and a plastic water barrel, they proclaimed we were running from a dust bowl.

The parents, it is true, were no strangers to adventure. They had escorted an elephant over the Alps in Hannibal’s footsteps. But that was eight year ago. They would not now have struck you now as a couple yearning to spend weeks under canvas without porters. A Boy Scout with a lot of badges for tying knots, decoding Ordinance Survey maps and making ovens out of mud and biscuit tins, I thought I had them sussed. “Bloody amateurs” I had called them on night one of our odyssey somewhere by the Rhine.

To reach the European mainland, we had loaded the car and ourselves onto a bulbous aircraft of a species now extinct that took us from Lydd in Kent to Ostend in Belgium. Hitherto, the parents had been serious nicotine addicts. When the flight attendant came round with the duty free, they were on the point of laying in a month’s stash of Kents. My father needed cigs to ply his trade. He was a seasoned foreign correspondent in more ways than one as the burn marks on his desk attested. Mother liked smoking’s erotic rituals. But all of a sudden, on the brink of an adventure very likely to be frazzling even if we didn’t knock anybody down they decided to go cold turkey. No pun intended.

Their love for each other was profound and passionate. As I would come to understand much later, they stoked their passion with alarming rows which they would then resolve in bed. Their fights were a kind of foreplay. Now, however, there being just one tent for the four of us, opportunities for the resolution phase would be sparse. Although or rather because smoke-free, the atmosphere in the cramped cabin of the Morris — the astronauts in an Apollo capsule occupied a ballroom by comparison — tended to grow more intense as each day’s drive wore on, generally combusting when it came time to pitch camp. Everyone would stomp off in different directions to decompress, except Charlie, who would put up the tent.

Our vehicle was built for English roads where they drive on the left, so its steering wheel was on the right, curbside, that is, once we were across the Channel. As we moved beyond the multi-lane world of autobahns and autostrade there was a lot of overtaking to be done if we didn’t want to wheeze along at 25 behind lorries spewing diesel smoke. But overtaking takes a toll when you cannot see what’s coming the other way until you are fully exposed to it and when, at the revs required to achieve escape velocity, your gallant but puny engine is screaming like a rabbit in the claws of a hawk.

We were in Bulgaria when it was decided we needed a break. We found a motel. The rooms were A-frame huts, each containing two single beds and not much else, a little seedy but at least Charlie didn’t have to put them up and take them down. We retired early. I couldn’t find my book and decided I must have left it in the parents’ hut. I barged in to find two fleshy pink forms wrestling about in the space between the beds. “What ARE you doing?” I asked in some amazement. It simply did not occur to me they would be doing that. For one thing, they were parents; for another, the coarse coir matting they were rolling on was surely not the ideal surface upon which to do it. Perhaps they had simply fallen out of bed. They made it very clear I was not welcome and I spent a sleepless night agonizing over what I had seen, only to re-ask the question as we drove off the following morning. “What WERE you doing?” My brother told me to zip it. Not for nothing was I known as the vile boy.

Emerging from breakfast in Plovdiv that morning, we found we had locked ourselves out of the car. Failing to gain entry with a coat hanger, we located a cobble stone and tried to break our way through a side window. A crowd gathered and seemed to enjoy the spectacle of bourgeois tourists smashing their property. The window refused to surrender. Finally, a spectator more versed than ourselves in the art of car theft stepped from the crowd with the appropriate tool and set us free.

As I look at the faded photograph, I am struck by the peacefulness of the scene. Peaceful is not how it felt then, and yet no mob of avenging Erinys had descended upon us, just the girl’s father and whoever it was that carried her from the ditch to the shade of the yurt.

My father, as I have said, was a seasoned foreign correspondent, a fireman in the parlance of the time. Wherever there was a war, a revolution or a coup, likely as not you would find him near the action. I have a picture of him with Mussolini’s corpse at his feet in Milan’s Piazza Loreto. He had been the first to report to the outside world that the Duce was dead. He did a lot of that. He was good in a crisis. Now he was faced with a difficult choice. The girl’s father indicated he was eager to let bygones be bygones for a consideration. The alternative was for Dad to have faith in his innocence, await the arrival of the gendarmes and let Turkish justice take its course. What if he accepted the father’s proposition and the gendarmes found out? Might that not be taken as admission of guilt? Dad reckoned it would. So when the police did finally show up, he surrendered himself and was marched off by a couple of constables with Lee Enfield rifles. Now was not the time to recall the caning scene in Lawrence of Arabia.1

What happened next is a bit of a blur but I do remember sitting with mother and Charlie in a dusty village police station waiting for events to unfold. The cops were not entirely unsympathetic. Mother, round and blonde, was catnip for many Turkish men. Someone was sent to bring us a large bottle of Coke, which he promptly dropped on the concrete floor when he returned. The explosion was impressive and went some way to relieving the tension. We were eventually allowed to leave, but without my father whom we would not see again until the next day. There was a British vice consul in the nearest town of any size, Çannakale, and we dined with him that evening. He was not at all reassuring, full of tales of English motorists languishing in jail without hope of freedom after fatal encounters with local pedestrians. Ours, thank God, had not been fatal.

Our passports were impounded and my father was given a date to appear before a magistrate. This let us to explore the Ionian coast and its spectacular ruins for far longer than we had originally planned. If you ask me why I chose to study classics through university to the exclusion of many more practical subjects, those glorious weeks are a big part of the answer.

The magistrate wasted no time finding in my father’s favor and afterwards invited him for coffee. “Mr Barber,” he said, “you would have spared yourself a lot of trouble if you had simply paid the girl’s father what he asked. That was to have been her dowry.”

Instead it was spent on my education.

I recently had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of Ahmet Kuru, professor of Political Science and director of the Center for Islamic and Arabic Studies at San Diego State University. He invited me to narrate his excellent book, Islam, Authoritarianism and Underdevelopment. I told him about the incident. He said the practice continues.

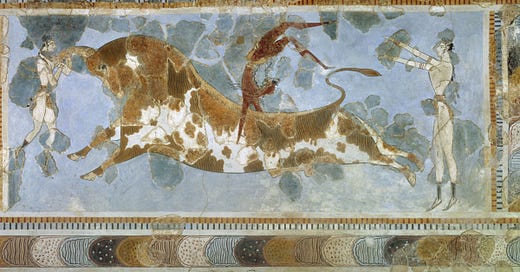

Some say the bull leapers of Knossos were originally from northwest Turkey.

In the scene, Lawrence is caned (in reality he was probably sodomized) and tossed by Turkish soldiers into the mud outside their barracks. A family friend, sadly no longer with us, claimed to have been Peter O’Toole’s stunt double for the muddy bit.

What a fascinating life Deirdre had! I loved this story.

Wow, what a tale! Worthy of Hesiod and his minx-y nymphs indeed!