Continuing the story of my great aunt.

England got Margery back from the Central Powers on March 7, 1916. As a volunteer orderly with a British Red Cross hospital unit in Serbia, she had spent close to a year with conscripts, wounded and whole, on both sides of the war. Many had been Austrians taken prisoner by the Serbs but that winter she and the rest of her unit had themselves become prisoners of the Austrians and Germans. She drew no distinctions between friend and foe. Had she been allowed, she would have stayed behind when her unit was escorted to Switzerland for repatriation. On the way out, she got chatting in her fluent German with an officer from the Kaiser’s Imperial Guard and charmed him into giving her and her colleagues a tour of Budapest between trains. When she got home, her father, Rev. Robert Barber, would recall, “her chief ambition was to nurse German soldiers to requite the kindness she had received and to satisfy herself that they were well treated.” She wrote to the War Office and received a “curt” reply suggesting she read the newspapers. The March 3 editions of many, both national and regional, had carried a Reuters interview with Dr Graham Aspland, a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He too was just back from Serbia where he had been captured while serving as surgeon-in-chief at the Anglo-Serbian hospital in Kragujevač. He said that he and his fellow prisoners (they included his wife) had been treated respectfully by the Austrians, good fellows who clearly wanted out of the war. The Germans, on the other hand, lived down to stereotype. Having interned all Serb men aged between 17 and 50, they had “cleared the country of everything they wanted, including 60 000 pigs and cattle”. To cap it all, they had no manners.

Every Austrian soldier, and even Austrian officers of higher rank than myself, always saluted me in the streets. The Germans never did so, but were always insulting. On the German-controlled railway, we had to travel in horse boxes, but as soon as we came under Austrian administration we were transferred to first and second class carriages…German officers jeered at their Austrian comrades and asked, “Why do you help the English swine.”

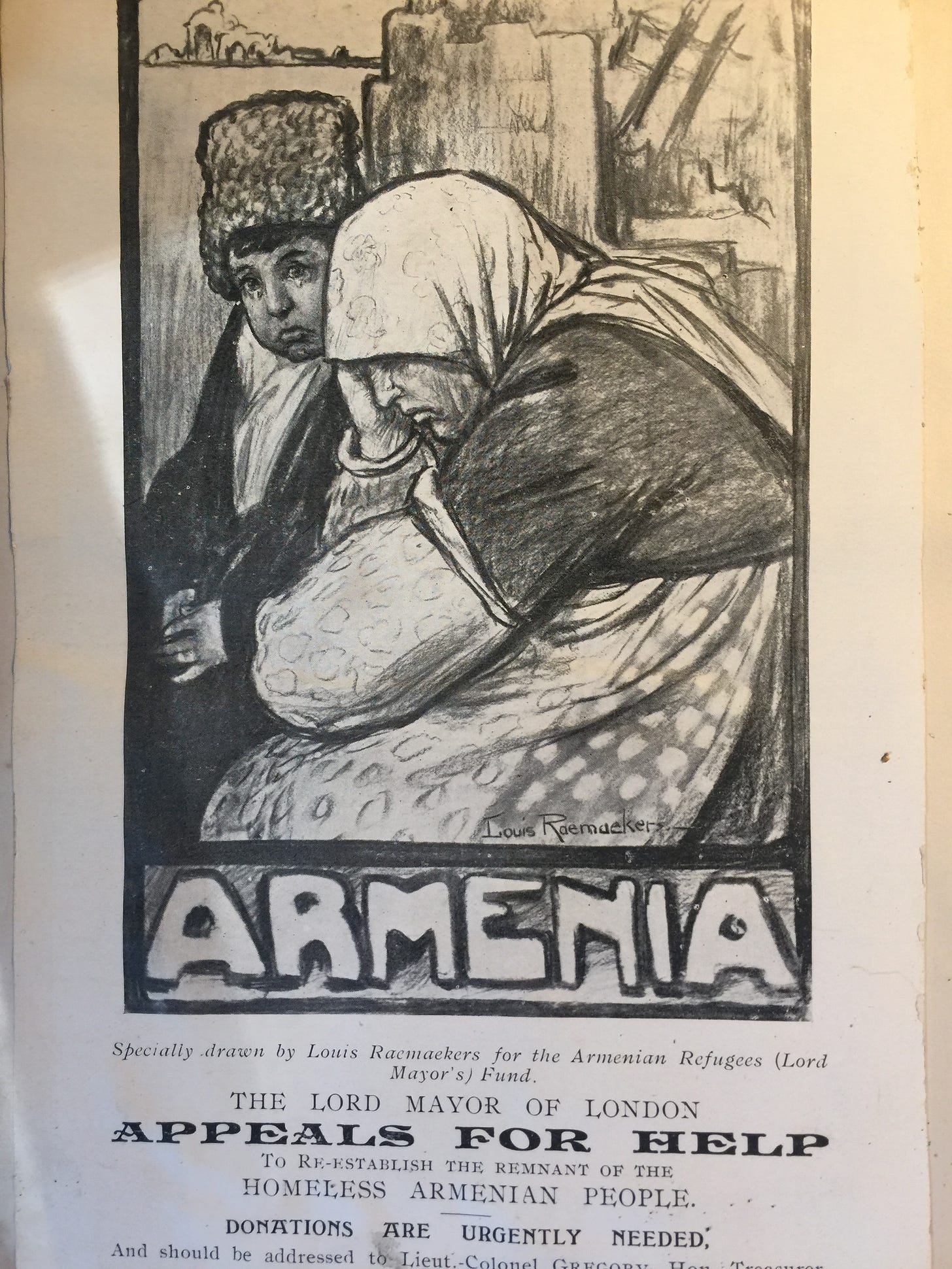

Margery set about looking for something else. The Red Cross had nothing. Neither, at first, did the Lord Mayor of London’s Armenian Refugees Fund. Then it changed its mind. She and her father were summoned to the House of Commons to meet Aneurin Williams MP, the Fund’s chairman. Would she be interested in joining a “Pioneer Party” the committee was sending to Armenia to assess what could be done for the survivors of the 1915 (and ongoing) genocide? “There are hundreds better qualified than I am who would give anything to go,” she replied, according to her father. “Never mind,” said the MP. “We want you.”

“We”, it turned out, included Dr Aspland who had signed on as the mission’s chief medical officer, and Beatrice Kerr who had been nursing in Kragujevač with the redoubtable Mrs Stobart. If they had not directly encountered Doña Quixota, they had surely heard of her. Perhaps it also helped that Rev. Barber was then the chaplain of Ely Cathedral. The Bishop of Ely was one of the Fund’s vice presidents. In the end, though, it was up Rev. Harold Buxton, the leader of the party and the Fund’s secretary, to pick his team. If there had been any objections to Margery, he must have overruled them.

Like Margery, Buxton had taken an emigrant ship to Canada early in his career, finding work as a farm hand in Ontario. The author of a glowing profile in Ararat, a London-based journal that described itself as “A Searchlight on Armenia”, thought it was to this experience that Buxton owed “that sense of sympathetic brotherhood with labour which is one of his chief characteristics.” Great-grandson of Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, the abolitionist, he took holy orders in 1904 and headed east to serve as chaplain of the Burma Railway Co., ministering to its employees on the line between Rangoon and Mandalay. Ill-health forced him back to England where he landed a curacy with his cousin, Rev. Conrad Noel, the famous Red Vicar of Thaxted who owed his living to Daisy Greville, Duchess of Warwick and founder of Studley, the agricultural college for surplus women that had helped set Margery on her way. Buxton’s brother Noel, MP for Norfolk North, was chairman of the Balkan War Relief Committee and an ardent supporter of Mrs Stobart’s Women’s Sick and Wounded Convoy Corps. Another brother, Charles, had become a Quaker and was making himself unpopular campaigning for a negotiated peace with Germany.

In a note to Margery’s father dated April 1, Buxton said he was “very glad the Lord Mayor’s Committee agreed to send Miss Barber…It will be a very interesting expedition and I hope we shall be able to render some good service to some of the war victims of the Caucasus. England is very largely responsible for what has occurred because she quarreled with the Russians and has bolstered up Turkish rule these many years.”

What had occurred, and was still occurring, was what the Fund, in an appeal published in the Times on April 6, called “probably…the greatest massacres recorded in history”. Islamic at its core, the Ottoman Empire historically granted a degree of autonomy to its populations of different faiths and cultures, but it had been crumbling for generations and the more it crumbled — the more it suffered defeat at the hands rebellious subjects — the more it began to morph into a religiously intolerant Turkic ethnostate, with a particular animus against Armenians. The Young Turk revolutionaries who ousted the last sultan in 1908 billed themselves as modernizers. That did not stop them also being enthusiastic ethnic cleansers. Looking to Germany to help them make Turkey great again, they sided with the Central Powers and went to war with Tsarist Russia, a traditional foe. Armenians living in communities across Ottoman Anatolia and the Russian Caucasus, two million of them on the Ottoman side of the border, were caught in the middle. They fought in both armies, but when, early on, the Russians gained the upper hand, the Young Turks demobilized their Armenians, took their weapons and set about getting rid of them altogether. Some one and a half million would be dead by the time it was over, slaughtered in place or on death marches to the Syrian desert.

Why did Buxton blame England? David Lloyd George, the prime minister, writing many years later in The Truth about Peace Treaties, supplies an answer: “Had it not been for our sinister intervention, the great majority of Armenians would have been placed by the Treaty of San Stefano in 1879 under the protection of the Russian flag…The action of the British government led inevitably to the terrible massacres of 1895-7, 1909 and, worst of all, the holocausts of 1915.” The Treaty of San Stefano ended a Russo-Turkish war in which the Russians ended up occupying Ottoman territory full of Armenians. Britain, not a friend of Russia at the time, helped the Turks retrieve its real estate in the peace settlement. Pro quo, the Disraeli administration extracted the the island of Cyprus as a quid plus a promise that Istanbul would be nice to the Armenians who were being returned to its fold. Cyprus the British would keep for 60 years. The promise went unkept.

The “very interesting expedition” Buxton had predicted began on the platform on King’s Cross station at 2.20 on the afternoon of April 7. Margery arrived with a large bag packed by her mother “with great ability, putting in just the right things,” her father would write. He was there to see her off. He painted her name on the bag as the train was about to leave. It had all been a bit of a rush. The right things included cobbler’s awls and carpentry tools.

Share this post