The story so far: it is 1915 and Margery, my great aunt, is now in Serbia as a VAD or Voluntary Aid Detachment orderly. She is with a British volunteer medical unit organized by James Berry, a surgeon from London’s Royal Free hospital, and his wife, Frances Dickinson Berry, an MD. They have set up shop in Vrnjača Banja, converting a canteen, various sheds and the Terapia, a sanatorium that brings to mind The Shining, into hospital wards. For manpower they have had their pick of POWs on whom, as underdogs, Margery has taken pity and whose load she strives to lighten. The POW’s are survivors of the rout Serbia inflicted on the invading Austrians the previous summer. Struck by her saintly eccentricity, the Berry’s dub Margery Doña Quixota. The typhus epidemic that brought the Berry unit and many others to Serbia at the start of the year is largely tamed by the time Margery arrives in April. Industrial scale slaughter is under way in France and the bloodlands between Russia and Prussia and the Turks are dashing Winston Churchill’s dream of thrusting into the soft underbelly of the Central Powers — Germany and Austria-Hungary — via the Dardanelles. Serbia is relatively tranquil. The Berry’s shift their focus to the health of the local population and begin to wonder whether they might not be more useful elsewhere.

Margery writes home in August:

Now my work is housework, my old trade…I make night nurses’ beds, then feed the chickens, then have breakfast, then interpret for the English cook and the Hungarian boy who helps in the kitchen, then see to the rooms. An old man is supposed to do this. We are taking civilian patients now, many of them children. One has been partly eaten by a pig. A doctor told me he saw a case of two children entirely eaten, all but their heads and hands and feet.

The Berry’s put their POWs to work improving the town’s dire sanitation. Their showcase project is a new slaughterhouse. Margery describes the laying of the foundation stone:

There was a service with priests and singing…The priests sprinkle the people with bunches of herbs dipped in holy water and the chief people are offered the cross to kiss while the priest dabs them on the head with the wet herbs. It was funny seeing the Princess’s little hat getting its dab.

The Princess is the consort of Prince Alexis Karageorgevich who had a decent claim to be king of Serbia after the previous one was gaudily assassinated in 1903 but has yielded to a more determined cousin. Now he is President of the Serbian Red Cross. His wife is the former Myra Abigail Pratt. She comes from Cleveland money. A golfer of some repute she took bronze in the 1900 Olympics. He is her third husband. She was his second shot at marrying an American. The parents of the first, Mabel Swift of Chicago, refused their consent, apparently because the marriage would have been Morganatic and she would not have become queen had he become king.

Margery continues:

Did I tell you about the grand concerts we had for three days? Austrian prisoners — three bands were taken prisoner — go round playing to get money for Serb officers’ widows. It was such a treat, except that they missed out German music. Still, we had Dvorak and the 1812 of Tchaikovsky. San Saëns’ Skeleton Dance was horrible in its new light; it made you think it was the poor fellows’ comrades dancing before them.

This will be her last letter until January 1916. Her father, Reverend Robert Barber, takes up the story in the Margery Book, the journal he keeps of his daughter’s adventures.

Soon after this, Serbia was invaded by the Austro-Germans from the North and the Bulgarians in the East and South. The Serbs confidently hoped for help from the Allies, indeed Niš was beflagged (with Union Jacks and French tricolores) under the impression that they were coming. Orders had gone forth to the Serbs not to engage in pitched battle, but to adopt rearguard actions and fall back — this in expectation of British help. It was very hard for the doctors and nurses to be reproached by the Serbs when help never came. They felt they had been betrayed.

The Times (the London one) of November 11, has this to say:

We shall probably almost immediately hear of the capture of Vraniatchka Bania'…the favourite watering-place of well-to-do Serbians in the summer. The enemy will perhaps triumphantly announce the occupation of the summer residence of Prince Alexis, the modest little Villa Agnesa, no more than a country cottage, and the buildings, Shumadia and Terapia, occupied by the British hospital units…It is understood that five units are already in the enemy’s hands.

Non-medical staff have the option of joining the Serbian retreat west toward Montenegro, Albania and the Adriatic. The stories of those who survive the trek over snowbound mountain passes clogged with starving refugees in the dead of winter will be the stuff of legend. Margery opts to stay. A colleague who makes it out will tell her parents:

Your daughter was divided between the joy of tramping it out through Montenegro and the excitement of being taken prisoner, and finally decided the latter would be the greatest experience. We left her in the best of health and excellent spirits.

On October 30, James Berry informs the secretary of his unit’s organizing committee in London:

Dear Mr Garratt,

I take this opportunity on the chance of getting a letter through by Mr. and Mrs. Gordon and Mr. Blease, who are trying to get home in Montenegro. In the last fortnight we have been extremely busy, I need hardly say, with crowds of wounded. Have seen no paper since Oct. 3, and news comes fitfully here.

We of course know that the Austro-Germans are advancing on us, and we expect them here within a few days.

All our party are very well, though not very pleased at the prospect before us.

Frances Berry puts it this way:

My dear Willoughby,

Probably long before you get this, we shall be prisoners in the hands of the Germans…We are all very depressed, and I really think our prisoners are about as depressed as we are.

The POWs, with few exceptions, have no interest in being freed and sent back to the front. Some who surrendered unwounded are afraid they will be shot as deserters.

The Austrians duly arrive on November 9, “without éclat or disturbance of any kind”, Frances Berry will recall in “A Red Cross Unit in Serbia”, a memoir co-written with her husband and other members of the unit.

Among the soldiers we came across, we found no shade of animosity towards ourselves as representatives of an enemy country…With regard to the behavior of the Austrian soldiers to the Serbian population, that was undoubtedly good…There were practically no stories of atrocities or deeds of violence, and little serious pillaging in spite of the fact that half starved soldiers were for many weeks wandering about the neighborhood and constantly begging for food…In our hospital Serbian and Austrian patients were on perfectly friendly terms…all the more suprising as the (Austrian) soldiers were largely Magyars and between Magyars and Serbs is longstanding animosity…It decidedly tends to show that the responsibility for atrocities is to be laid at the doors of those in authority more than the perpetrators, and that if the “bête humaine” is present in most most natures it requires not merely letting loose, but considerable prodding before it comes out of its hidden dwelling place and displays its horrors.”

From Rev. Barber we learn that Margery was not to be denied Christmas:

Christmas came when they were still “prisoners.” Margery was determined to have a Christmas tree. She and a Serbian orderly went round the cottages and homesteads and managed to purchase small quantities of meal collected in a pillowcase. An Austrian canteen obliged them with 2 lbs of sugar which cost 16 shillings (an astronomical sum), walnuts, leaves of tobacco in bunches, boxes of matches, a little tinned milk, and rice. These were made up into sweets of sorts. This supplied their Christmas dinner and Christmas tree. Margery cut up the top of a biscuit tin…into sconces to hold candle ends fixed on the tree.

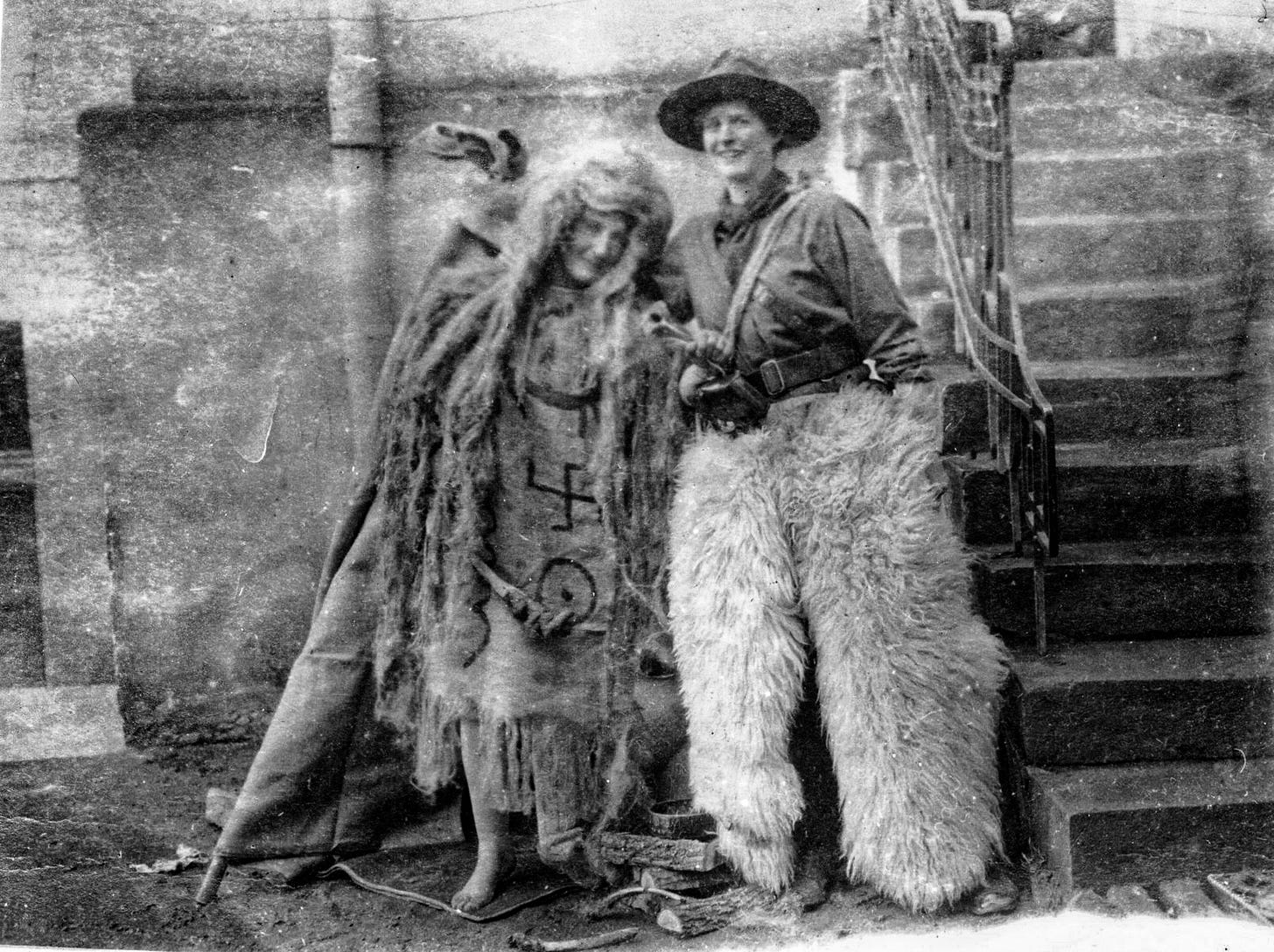

The festivities include fancy dress — Margery puts together an impressive cowboy outfit — and amateur theatricals in which she is assigned the lead. Frances Berry again:

We dramatised the story of Pepelyouga, the Serbian Cinderella, culled from Petrovitch's "Hero Tales and Legends of the Serbians," and wove into the drama allusions to other Serbian myths and national heroes. With the help of costumes and spindles borrowed or bought from peasants, and with Pirot carpets on the walls, the setting was made as typically Serbian as possible. Doña Quixota made her debut as an actress in the role of the heroine. She threw herself into the part and quite scored a triumph, but it took some coaching and persuasion to induce her to condescend to accept in a proper spirit any lovemaking from the Prince, or to sacrifice her democratic prejudices so as to appear in jewelry and silk attire. However, the fact that these were Serbian and not British mitigated the humiliation.

Cowgirl and Indian

On January 3, 2016, a postcard reaches the Barbers, now in Ely, the cathedral town north of Cambridge.

Dearest Mith, Having a lovely time. Would not have missed it for anything. May be sent home soon, so look out for another job for me. Your loving Margery.

A letter follows.

Dear Mith,

We now hear we may be sent home soon. I do not want to come home yet so if I get a chance, I shall join another Hospital and nurse Serbian prisoners or Austrian soldiers. I and three sisters want to stay on and do a little more now we are here. But if I have to come home with the rest please be on the lookout for another job for me. Love to all. Do you hear from Peter? It’s the Serbian Xmas tomorrow. They eat a pig and put straw on the ground in the cottages, but I will tell you a lot when I come.

Love from Marg

The Berry party, now 25 strong, sets out by train on February 21. Grateful Serbs give them a roast pig for the journey. Accompanying them as far as Vienna are two guards, “very pleasant fellows”, the Berry’s feel, Hungarian, a prosperous farmer and a traveling salesman in civilian life. The salesman owes this cushy billet to heroics. When the Austrians were thrown back across the Save river the year before, he swam his general to safety though himself wounded.

Rev.Barber adds a detail:

During the railway journey, Margery disarmed one of the guards in charge of the party by seizing his bayonet and with it cutting up some chocolate which she gave him.

At some point before the party reaches Budapest, Margery, in her father’s telling of it, makes friends with a German officer carrying dispatches from Constantinople:

She asked him, as he graciously claimed ancient Teutonic relationship, whether he could arrange for them to see round the town. This he seemed most proud to do.

The Berry account is fuller but does not mention Doña Quixota’s role in chatting up the officer.

We were agreeably surprised by the entry of a pleasant young man in the uniform of the German Imperial Guard and wearing the Iron Cross. He sat down among us and stayed a long time, telling us he came from Hamburg, which was “half English”, that he has visited England many times in his yacht, and had played in a championship tennis tournament at Wimbledon. “The English and Hamburgers are cousins,” he said, “for the English came from our neighborhood,” which was true enough as the original Engel-land was close to the mouth of the Elbe. He spoke almost perfect English and took such a fancy to our party that upon arrival at Budapest he insisted on taking nearly the whole Mission to see the sights of the town while our luggage was being transported to another railway station.”

We’ll let Rev. Barber close the Serbian chapter of Margery’s life.

Margery arrived home, at Ely, March 7, 1916, little the worse for her experiences. She had contracted a chill on the very cold journey through Europe — snow all the way. And no wonder, for we found out afterwards that she had parted with most of her underclothing to give to another nurse.

We learnt of this through her uncle Fred W. Barber, who at Fulham Military Hospital, on May 25, 1916, met Nurse Murfy, late member of the 2nd British Farmers’ Unit which had been working in Serbia.

“She was tremendously enthusiastic about Margery and said she and others could never forget her kindness. M. did no end for them, and must have denied herself in order to supply underclothing and other necessaries.”

She remained in England for less than a month. Her chief ambition was to nurse German soldiers, to requite the kindness she had received, and to satisfy herself that they were well treated. She wrote to the War Office for information on this [score], and received a curt reply, referring her to the public press.

Next: Armenia

Share this post