Margarita Robertovna, as she is known locally, is writing to her mother, who knows her as Margery. She is squeezing as many words as she can onto a sheet of coarse grey paper, the squared kind for doing sums. First the date. November 14, 1931. Then, carefully printed, her address.

Урал Каз Край Рыбак Союз, Цалкарский Промысел, Анкотуиского Район.

Copied correctly, this will direct her mother’s reply forty unpaved miles across the steppe from Uralsk in the northwest corner of what has lately become the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Her own letter is bound for 6a, The Leas, Folkestone, Kent, a clifftop row house with an occasional view of France.

“Dearest Mith,” Margery writes. “Here we are in our new home. Robert and I are delighted with it.“

Robert is her five-year-old. She calls him Robert to family and friends from her former life. Here the boy goes by other names. She thought of calling him Karl Marx but settled on Kompro, short for Communist Proletariat. Komok is the diminutive she uses. To his playmates he is Kolya. Robert he inherits from Margery’s late father, an Anglican vicar. He is a good-looking boy. His mother worries he is small for his age. His arrival in the world had not been easy.

They have their new home to themselves. It consists, Margery writes, of “a large room with a window and a door at one end and 2 windows at the other. The door leads onto a good porch with a nice food cupboard and place for our hen and cock, and the porch and window look onto the courtyard of the Promisel or Fish Farm; the other two windows look out onto the steppe with a Khirghiz village. They live very scattered so that only 3 houses are visible.”

The Khirghiz (Margery’s spelling) are nomads. Or were. They have pastured their herds across the vastness of Central Asia for centuries. Now they are being “sedentarized” under Stalin’s First Five Year Plan. Moscow has decided they must pack up their yurts, settle down and surrender their livestock. This is contributing to a famine across the Kazakh Autonomous SSR that will leave one and a half million dead over the next two years.

“Our side walls are inside walls,” Margery continues. “On one side is the head man’s rooms and on the other the “salters” — these are Russian — and the baker, an old man without any family, also Russian. All the rest of the personnel and workers are Khirghiz. Needless to say, I am trying to learn to talk to those as they know no Russian! The head man has a nice wife with 4 children, the eldest boy older than Robert. The latter is as happy as possible, playing with the little Khirghiz as well and learning Khirghiz fast.”

Margery turns to the subject of food. In Uralsk, to which they moved in 1926, she and Pyotr, the boy’s father (Peter to Mith and hereafter), wrestled calories from the soil, a few chickens and, until it was socialized, a cow. The steppe is merciless even if you know what you’re doing. The little family has been fortunate that a bit of Margery’s money still reaches them from England via Quakers in Moscow. She has money because her mother is a Guinness of the brewing and banking Guinnesses.

“We have as much fish as we can eat — fresh, salted and kippered. I saw the kippers being smoked today. They reminded me of the pictures of Dante’s Inferno.”

The fish come from Lake Chalkar, a brackish, egg-shaped puddle left, some say, when an ancient ocean retreated south into the Caspian. The name comes from a Kazakh word for big. The lake is seven miles long and five miles across. At this point Margery thinks it is 50 miles by 50, an easy mistake. The steppe here is as flat and empty as the ocean. From its treeless shore, Chalkar could be as broad as the Pacific if you knew no better. Big or small, it “teems with fish” — carp, bream, pike and, most prized, chekhon, an oily cousin of mackerel.

“The fishermen — various kolkhoz groups or parties — come and fish, sell their fish to us and are entitled to buy all sorts of goods ad lib for their fish money. So we have a nice shop.” A kolkhoz is a collective farm. “Us” is the Ural Kazakh Fisherman’s Union which does the salting and kippering and runs the store. There is no refrigeration. That would call for electricity. Peter is keeping the books. He would rather be studying accountancy in Moscow but they didn’t accept his application. Still, for the first time in their six years together he and Margery will be well supplied as winter sets in. Or so she wants to reassure her mother.

“Peter bought a good warm overcoat with his first 1/2 months wages and 400 lbs. of potatoes, and tea and sugar, tobacco, paraffin, soap, onions — 26 lbs. — and tomorrow will receive wages to buy boots, more potatoes and materials so I shall be busy on my machine.”

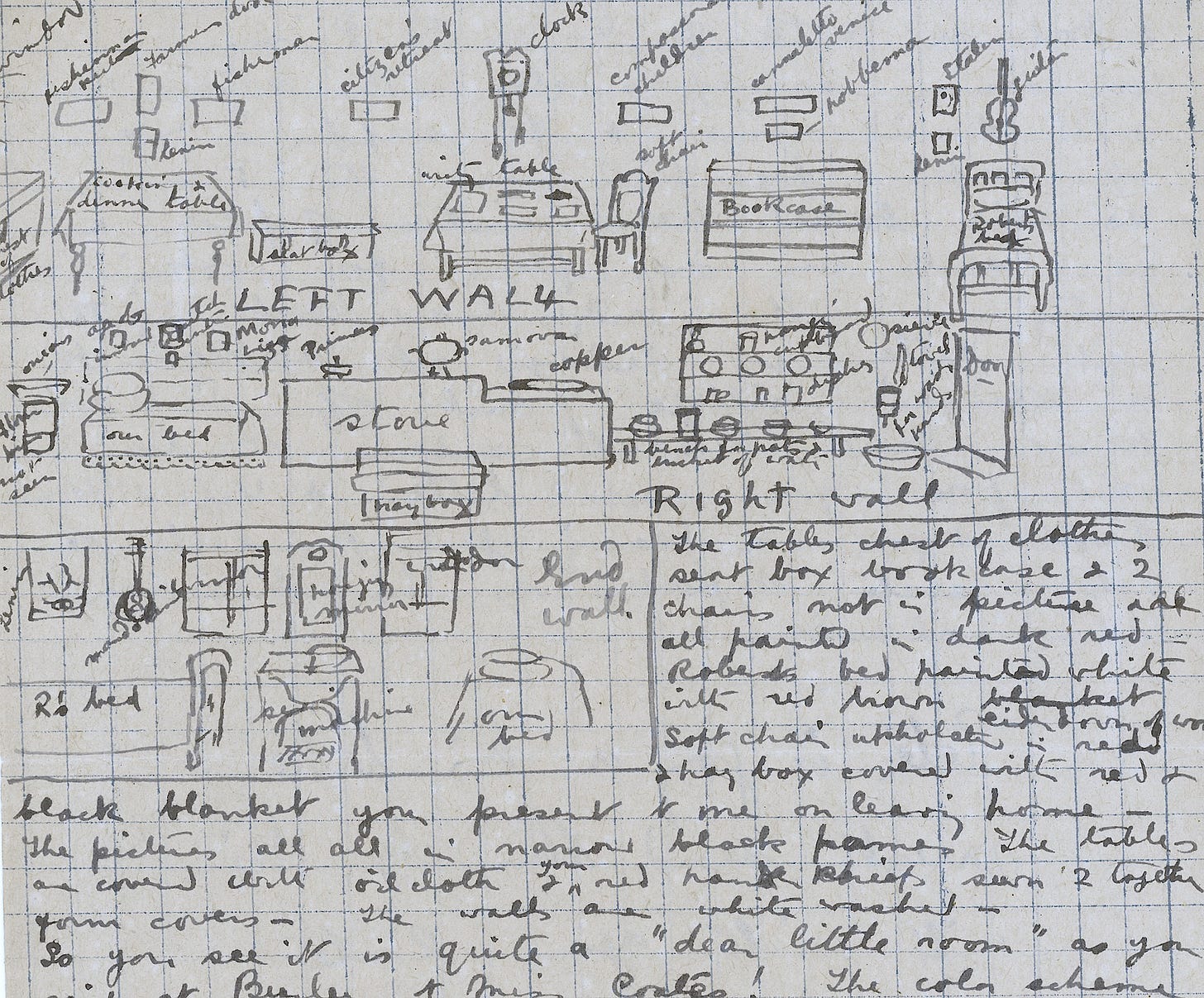

She draws a diagram of the room, labelling its contents. Her pedal-powered sewing machine sits between the windows at the back. She makes and mends with whatever she can find. To the right is the bed she shares with Peter. Onions and flour are stored at the head. At the foot is the stove. Built of mud and stone it takes up nearly half the wall they share with the salters. On top sit a Primus, a samovar and a copper. Between the stove and the door are buckets and a bowl for hands after visits to the communal pit latrine.

“Fuel is free, as much as you want — sheaves of rushes from the banks of the lake. I burn 2 sheaves in the early morning, putting my saucepans to one side on bricks and tripods and stuff the rushes in beside them. The copper boils while you burn them and you have hot water for washing. I then take out the breakfast saucepan and put it in the hay box and close up the stove after putting in pies or something to bake.”

Against the left-hand wall is a kitchen table. On it is a cloth stitched together from colored handkerchiefs. These were sent by Mith. Anything more elaborate than a hanky or a pillow case is subject to taxes Margery and Peter cannot afford, or may disappear en route. Then come the table Margery is using as a desk, and a bookshelf. It holds well-thumbed medical and veterinary handbooks, Bukharin’s ABC of Communism, and copies of Wife and Home, a decidedly bourgeois monthly for young English mothers to which Mith has subscribed her daughter and which, remarkably, arrives like clockwork even when nothing else does. After the bookshelf, there’s Robert’s bed, across from his parents’. Above it hang pictures of Lenin and Stalin alongside Peter’s guitar and mandolin.

Also on the walls — whitewashed brick — are a clock, two more Lenins and a medley of mezzotints: a Canaletto of Venice, Hobbema’s Apollo, Courbould’s The Fisherman’s Departure and the Fisherman’s Return, and scenes of Jane Austen-era country life by William Wade: The Compassionate Children, The Citizen’s Retreat and The Farmer’s Door. Here Wade’s farmer would have been classified as a kulak or rich peasant and, had he been allowed to live a while, worked to death in a labor camp; the horses whose noses the compassionate children are stroking would have been “socialized” by the kolkhoz.

Over the sewing machine is a mirror. In it, Margery sees a woman of aristocratic bearing and vestigial beauty. At 44, she has weathered surprisingly well given the vicissitudes to which she has subjected herself. Had she lived the life to which she was born, she would still have the teeth she has lost as a complication of tuberculosis and other assaults on her immune system.

“So you see,” she tells her mother, “it is quite a dear little room.”

It is time to finish. The nearest mail box is seven miles off. Peter is going on his bicycle. He likes an excuse to be out of the house. “Must send this by him. Will write again later. Love from Marg. And kisses.”